This is part one of a four-part series on the life, death and safety legacy of Dale Earnhardt, 20 years after his death at the 2001 Daytona 500.

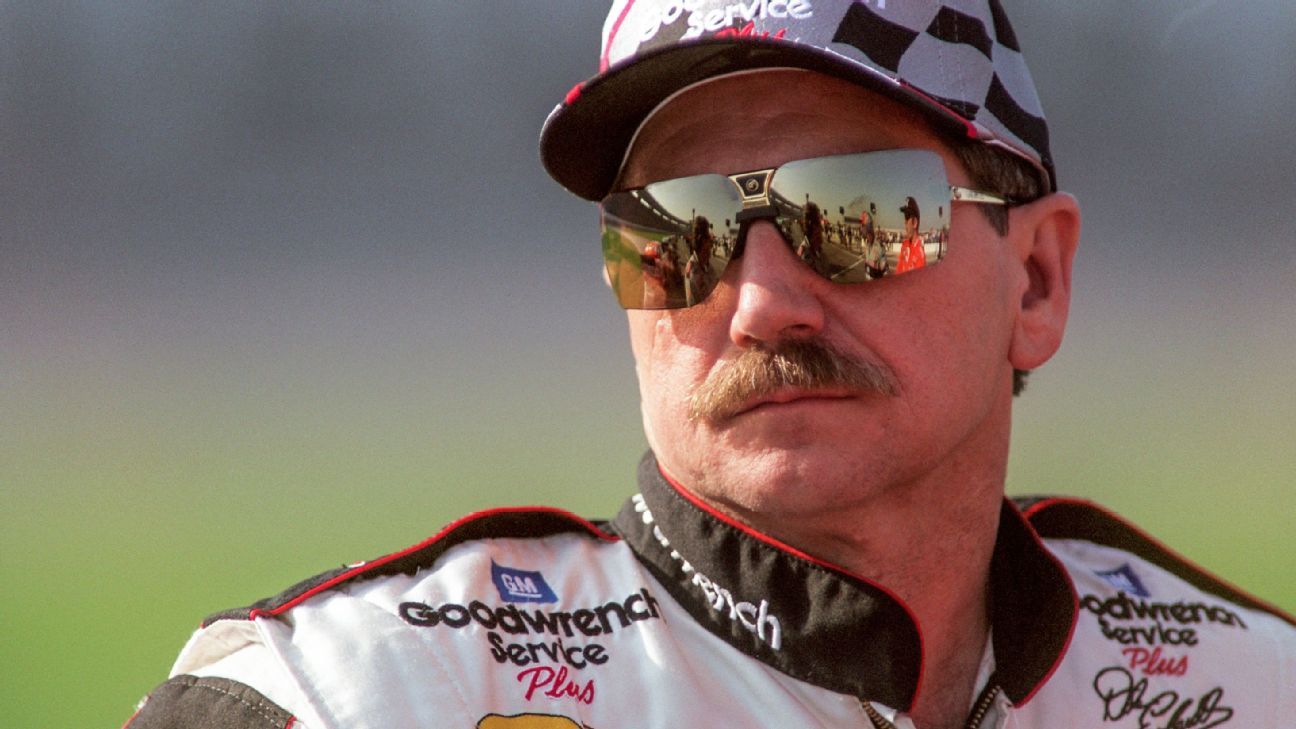

THE INTIMIDATOR STANDS watch over his hometown of Kannapolis, North Carolina, day and night, his arms permanently interlocked across his chest, his folded Gargoyles shades sticking out of his shirt pocket, as visible as the Wrangler “W” on the back of his jeans and the seams in his favorite cowboy boots.

It is a frosty February afternoon, and the statue of Dale Earnhardt is staring into the face of a hard winter wind like it was a rival on the racetrack. The smirk that peeks out from beneath his signature mustache says, “C’mon, man, is that all you’ve got?”

The 9-foot-tall bronze statue is, appropriately, larger than life. To those who were around him in person, those devotees who work to keep alive the Gospel of The Intimidator, including the man who carries Dale Earnhardt’s name, that’s the way his legacy feels.

“It’s huge!” Dale Earnhardt Jr. says with a hearty laugh. “It’s amazing and I’ve loved the opportunity to take [my wife] Amy there, to take my daughter there. When you see other people visit it and post their experience online, it’s a great thing.

“But those are just momentary sorts of things. They’re not forever. They’re not the memory. It doesn’t replace the memories, you know?”

The 2021 Daytona 500 is Sunday, and Feb. 18 marks the 20th anniversary of the day NASCAR’s biggest star was killed in the final turn of the final lap of the race he loved more than any other. This Great American Race will be no different than all the others run since 2001, as the pall cast by the death of Earnhardt at age 49 has never gone away. But the milestone date has made this year feel especially heavy.

Twenty years without Dale Earnhardt on the racetrack with his hands on the wheel of his famed No. 3 Chevy. That’s a lot of time to process the legacy of the legend. Twenty years means the number of people who have watched NASCAR without Earnhardt might very well equal or be greater than those who watched races with him in the field. With each day and race, the images of Earnhardt become more aged. The videos of his 76 wins are in standard definition. The photos of his seven NASCAR Cup Series championships are on film. There have been 719 Cup Series races without him, an entire generation passed, and enough time for dozens of racers to have debuted and retired.

His untimely death still reverberates within the sport and beyond. In a four-part series in conjunction with E:60 (Sunday, noon ET), we examine the racing risks Earnhardt knew all too well and the sacrifice of a superhero life that has since saved so many others: his rivals, his son and Ryan Newman in the Daytona 500 one year ago.

But first, one must understand Earnhardt’s colossal effect on stock car racing itself. His handshake was like a pneumatic vise grip. He played mind games like Muhammad Ali, owned corporate boardrooms like Peyton Manning and walked into the racetrack every Sunday with the swagger of Tiger Woods. Drivers who raced against him at Talladega and Daytona even claimed he could see air.

It’s all true. Every bit of it. Dale Earnhardt wasn’t a stock car racer. He was the stock car racer.

WHEN EARNHARDT WAS alive, he was often compared to a fellow North Carolinian also at the height of his stardom: Michael Jordan.

As we experienced last year with the airing of “The Last Dance,” propping up an athlete from back in the day as still being the GOAT can lead to pushback from those who never saw them compete.

But those who wonder why Earnhardt is such a big deal didn’t see the life those of us above a certain age witnessed. They didn’t see him as a rough-hewn rookie in the 1970s, a kid from the mill hill who could barely talk on camera, pissing off the likes of Richard Petty, Cale Yarborough and Bobby Allison with a chrome horn the size of the Carolina Piedmont and an attitude to match. They didn’t see that brash, bushy-faced young man whom those legends tried to lecture about playing fair, who then walked up and seized their stock car kingdom right out of their gloves.

They may have been born too late to witness 1987’s “Pass in the Grass,” when Earnhardt snookered Bill Elliott and Geoff Bodine to win the NASCAR All-Star Race … or the time at Richmond when he told his team he was going off the radio for a minute and then drove by them on pit road as he climbed out of the window to clean off his windshield, driving his Chevy with his knees … or when he wrecked Rusty Wallace and Terry Labonte at Bristol ’95 and shot his smirk at Wallace when the fellow future NASCAR Hall of Famer angrily winged a water bottle off Earnhardt’s head … or heard him say this when he was asked by a reporter about chatter that the sanctioning body was going to slow the cars down: “If you’re not a race driver, stay the hell home. Don’t come here and grumble about going too fast. Get the hell out of the race car if you’ve got feathers on your legs and butt. Put a kerosene rag around your ankles so the ants won’t climb up and eat that candy ass.”

Earnhardt is the man Hollywood was trying to re-create in “Days of Thunder” baddie Rowdy Burns. The filmmakers even tried to talk him into playing the part himself because they didn’t think anyone else could pull it off.

He is the man of four nicknames: Ironhead (which was not a compliment), One Tough Customer (thank you, Wrangler), The Man in Black (thank you, GM Goodwrench) and The Intimidator (thank you, sportswriters, for all those T-shirts sold).

“He’s dead and been gone for 20 years. The stories, you’ve heard ’em all, right? But maybe you haven’t.”

Dale Earnhardt Jr.

Earnhardt was a pioneer among professional athletes who trademarked their signatures and image, and the first auto racer to do it — a high school dropout (his greatest regret) who built a business empire estimated to be worth half a billion dollars when he died. He founded his own merchandise company and ended up handling souvenir sales for nearly all of NASCAR’s other stars, including his fiercest rivals. A decade after his death, he was still the second-best-selling driver when it came to merchandise, trailing only his son of the same name.

He won 34 races at Daytona, from all-star shootouts to the 1998 Daytona 500. He won nine times at Darlington Raceway. He won a record 10 times at Talladega Superspeedway, including the last of his 76 career victories in 2000, when he dashed from 18th to first over the race’s final six laps. That otherworldly final Earnhardt win capped off a runner-up finish in the championship standings, at age 49.

He raced with broken legs and collarbones. He won the pole at Watkins Glen and nearly won the race with both a broken collarbone and separated sternum. He knocked down trees with a bulldozer. He worked his farm and tossed hay bales around like beach balls, even when he could afford to hire an army of ranch hands to do it for him. He routinely pulled his truck off the road to shoot a deer on the horizon of his property that no one else riding with him could even see.

“Someone will ask me, you know, explain to us Dale Earnhardt,” says Mike Helton, former NASCAR president and the man who often found himself on the receiving end of an Earnhardt rant. “Explaining Dale, that’s like trying to explain John Wayne or Neil Armstrong or other heroes from that era that you can no longer experience.

“… But you still try to explain it, because there was no one else like him. Never will be.”

EVEN ON A February day as cold as this one in Kannapolis, there are still a couple of cars each hour that come to see the Dale Earnhardt statue. The visitors almost always come in pairs, an older race fan with a youngster in tow. The elder tells stories as they point to the centerpiece of Dale Earnhardt Plaza, located just off Dale Earnhardt Boulevard, somewhere between Dale Earnhardt Incorporated, the glass-covered HQ once touted as his “Garage Mahal” and the row-house neighborhood known as Car Town, where his mother Martha still lives.

The statue is a short walk from the site of the textile mill where his father Ralph once walked off the job to go race full time, and a short drive from the roadside cemetery where Ralph eternally rests beneath a headstone decorated with an etching of his race car. The mill site is now home to a minor league ballpark, home of the Kannapolis Cannon Ballers, the team Earnhardt once co-owned (they were the Intimidators then) and whose daredevil mascot still sports a familiar mustache.

“I love to stop by there and I love when people tell me about going by there,” Earnhardt Jr. says of the rejuvenated area around his father’s bronzed likeness, the crown jewel of what the local tourism board promotes as the Dale Trail. “But you know land becomes valuable, land finds new purpose. Statues like that are moved to other locations and could disappear altogether one day, so I don’t, I don’t invest a lot of emotion in it.”

So, what does he invest in?

“Items, photographs, whatever I can find that keeps me connected to Dad, and I have invested a lot in that. Just ask Amy.”

Earnhardt Sr. memories have become Earnhardt Jr.’s stock in trade. If you’re on an internet auction site late at night and find yourself losing a bidding war over Intimidator memorabilia to someone with seemingly bottomless pockets, there’s a better than average chance it’s against his son. Over the past half-decade, in particular, he has been on what he describes as “a quest” to locate anything his father wore, raced or built.

He gleefully describes tracking down an early 1980s Chevy Nova his father raced in the NASCAR Busch Series, a find he verified when his uncle said there would be a handmade driveshaft loop. When he rolled up under the car, there was a handwritten note, “Handmade by Dale Earnhardt.” Later, he and his mother were digging through a box of old photos and there he was, a little boy, sitting behind the wheel of that same car. Now he sits in that same seat, having fully restored his father’s ride.

He pulls a firesuit he purchased online from a vacuum-packed plastic bag. It was worn by his father in Victory Lane more than a quarter century ago, and the son immediately takes a drag off the clothing. He calls Amy over: “Smell this!” It still holds the scent of beer and Winston cigarettes.

He found one of Senior’s uniforms from his Rookie of the Year and title-winning seasons of 1979-80 by accident, stuffed in a trash bag that was about to be thrown out as he was emptying an old family storage unit. Sometimes he slips on a pair of boots his dad wore for years, footwear the old man loved so much he had them resoled dozens of times.

“He wore boots like I wear tennis shoes, just all the time,” he says. Now Earnhardt Jr. will wear them around the house from time to time, just to walk a little bit in his father’s shoes.

“It’s kind of like doing your genealogy in your family tree. There’s no end, right?” he says, describing his scouring of NASCAR fan accounts on social media, especially those that post classic photos. If he finds one of his father that he has never seen before, he’ll reach out to thank them.

“I try to contain my excitement because I know it’s kind of weird to be that excited over something so silly, but you’re like, this is amazing! I just learned something new about my dad!” Earnhardt Jr. says of those moments when he sees Senior wearing a uniform he’s never seen, a sponsor he didn’t know about or a moment he wasn’t aware of. “You’re not expecting to learn new things about him at this point. You know, he’s dead and been gone for 20 years. The stories, you’ve heard ’em all, right? But maybe you haven’t.”

SOMEONE ALWAYS WANTS to share their Senior memories with Earnhardt Jr. Heck, it happens even when he doesn’t leave the house. The UPS man delivering those eBay packages, the plumber, the pool cleaner … anyone who stops by, they have this look on their faces whenever they have Earnhardt Sr. stories they want to pass along.

It was like that when Junior was a kid, when he was a teenager breaking into racing, and certainly when he became the “next big thing” in the NASCAR Cup Series, employed by his old man. Back then, it was too much. The Intimidator experience was overwhelming.

“When I was a little boy, he was Dad at home and he was Dad at the track,” Earnhardt Jr. recalls. “But then, as I got older and I started to see the Dale Earnhardt in him that everyone else was seeing, right? He was still Dad, but I also was starting to see this icon, and this hero.

“And I would even look at him that way, like fans would look at him. I would be, like, intimidated by him, nervous to be in the room with him and, uh, feel inferior to him, you know and all these unhealthy things, right? I’m his son and he just got so big.”

As a result, the true father-son moments became harder to come by, even when Earnhardt Jr. started driving for his father in the Busch Series in 1996 and moved up to Cup by decade’s end. When he sees TV commercials or an interview they did together, he recognizes that intimidated look in his eye and says that he wishes he had taken a deep breath, made himself relax and enjoyed those moments more.

Only at the end was he figuring out how to feel differently.

“We had a moment on pit road of the 2001 Daytona 500 when he grabs me by the neck and he’s like, ‘Hey man, we’ve got good cars, take care of your car and we’re gonna have some good finishes,'” he says. “And that was like a super Dad moment.”

Of course, the Earnhardts didn’t know that would be the last time they talked. They simply thought Feb. 18, 2001, was just another race day. But in three hours, their lives and the lives of everyone on pit road at that moment would be changed forever.

Part II of this four-part series continues Wednesday with a look at the culture of motorsports safety in the years leading up to the tragic 2001 Daytona 500.