When the Tampa Bay Rays first tasted success, reaching the 2008 World Series after just 10 years in existence, then-manager Joe Maddon would often remind his team that the franchise was still in its infancy.

“We are where some other teams were 100 years ago,” Maddon would say. “We’re writing history. We’re the first chapters of that history that people are going to look back on.”

The Maddon-led Rays lost to the Philadelphia Phillies in that Fall Classic, and the team has still never won a championship — under him or any manager — but after all of these years, dating back to the team’s inaugural season in 1998, the time could be now to change franchise history forever.

Win or lose this week, though, the American League champion Rays have long been changing baseball history with an innovative approach to team building, led by a brain trust whose members have now spread to front offices across Major League Baseball — including to the team they just beat in the American League Championship Series, the Houston Astros, and the team they’re battling now for the Commissioner’s Trophy, the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Now in 2020, the brainiest baseball team in the bigs is four wins from its first title.

“Are we doing things the right way?”

Between meetings, between conference calls, this question has long bounced around the baseball operations offices of the Rays. Under the leadership of former Wall Street analyst Andrew Friedman — who in 2014, after a decade with the team, left to become the president of the Dodgers — the group developed a reputation for maximizing the potential of its players, creating a strong farm system and making shrewd trades. It helped produce stars like super-utility man Ben Zobrist and ace Chris Archer — flipping the latter a couple of seasons ago for two of the most important members of this year’s pennant-winning club, 6-foot-8 righty Tyler Glasnow and outfielder Austin Meadows.

Tampa Bay hasn’t always succeeded, particularly in an AL East that features perennial winners in the big-spending New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox, but for the Rays doing things the right way — in a new way — has meant embracing the opener in their rotation, using extreme shifts and sometimes even a fourth outfielder. Despite a payroll that ranks 28th in MLB, ahead of just the Pittsburgh Pirates and the Baltimore Orioles, that philosophy — along with a reputation for outsmarting other teams in trades and tactics — has long brought the Rays respect. Now it has brought them back to the World Series.

With a roster that has few, if any, household names, the hallmark of the 2020 Rays — as it has been for the club for many years — is depth.

“Working with Andrew Friedman, depth was always something that was critical to our organization,” Erik Neander, the senior vice president of baseball operations and general manager, told ESPN.com earlier this year. “For health and also for unexpected performance in both directions. Depth is a way to have guys who can surprise you in pleasant ways. In this division, we usually don’t bully clubs with the top of our roster. It’s really about flattening the talent slope from spots five through 40, making sure we’re strong there.”

After Friedman’s departure, the unorthodox approach to franchise building and willingness to stretch the impact of analytics on the field continued with an all-star quartet of executives, including Neander. Matthew Silverman started his career at Goldman Sachs, where he helped Rays owner Stuart Sternberg structure his bid for the team before being hired as its president. Senior vice president of baseball operations (now Red Sox chief baseball officer) Chaim Bloom wrote for Baseball Prospectus before joining the Rays as an intern. Current Astros general manager James Click also rose from Baseball Prospectus writer to intern, then all the way to vice president of baseball operations with Tampa Bay. Together, they developed a front-office culture where decisions were collaborative, nontraditional ideas were embraced and negative reaction from others outside the organization was largely ignored.

“Try to appreciate the strengths a player possesses at any given moment. … You don’t necessarily know what [paths] they’re going to take, but the more options, the more possibilities, the more you have a chance for them to take that step. It’s easy on any given player to focus on what they can’t do, especially prospects.”

Rays GM Erik Neander on scouting and developing players

Not that being in St. Petersburg, Florida, hurt. While the front office sometimes faced blowback from the national media regarding some of its forward-thinking moves, the lack of the daily scrutiny found in larger markets like Boston, New York, Philadelphia or Los Angeles meant more room for experimentation, according to former Rays executives — not to mention the necessity to be creative with money. That relative freedom is something Rays alums say they’ve come to appreciate after moving on to bigger markets.

In recent years, the success of Tampa Bay brought attention to Bloom, who interviewed with the Phillies, Milwaukee Brewers, Minnesota Twins, San Francisco Giants and New York Mets before taking the job in 2019 running the Red Sox. All of the final four teams in this year’s playoffs — the Astros (Click), the Braves (team president Alex Anthopoulos worked under Friedman in L.A.), the Dodgers and, of course, Tampa Bay — have roots and ties to the Tampa Bay organization. Now, Friedman faces off for a World Series title against a team he knows as well as anyone.

“Obviously, I have close personal relationships, my closest friends, but my focus is what we’re doing here. We came back down from 3-1 and our focus is on tonight, and now our focus is four more wins,” Friedman told Tom Verducci after the Dodgers won the NLCS.

Said Click to the Houston Chronicle, about facing his former team in the ALCS: “On a scale of zero to weird, it’s pretty weird.”

Click also told the Wall Street Journal: “The ability to create your own talent is always going to be a huge mover. It’s something that the Rays obviously do exceptionally well. It’s something the Dodgers do exceptionally well.”

With smarts, the ability to fly under the radar to a degree and financial restraints that would often necessitate innovation, ideas that would start as watercooler topics — hypotheticals thrown around for fun with coworkers — have turned into radical ideas actually implemented by the Rays on the field.

One of the more recent radical ideas: hiring baseball’s first process and analytics coach and giving him a spot in the dugout. Jonathan Erlichman, a former math major at Princeton — nicknamed J-Money by Friedman for his conspicuously sharp dressing in his early days with the team — rose from Toronto Blue Jays intern to the Rays’ director of analytics before being named to the coaching staff prior to the 2019 season.

Most famously, before the 2018 season, the Tampa Bay front office, under the leadership group of Silverman, Bloom and Neander, wondered whether having a five-man rotation and a traditional bullpen with a closer was the best way to maximize the talent of their roster.

The opener was born — and suddenly, the entire weight of an idea would fall onto the shoulders of then-35-year-old right-hander Sergio Romo. After experimenting by using more under-the-radar relievers like Andrew Kittredge, Ryan Yarbrough and Yonny Chirinos to start games early in the season, the Rays saw Romo, with nearly 600 appearances under his belt, as a way to legitimize the practice. Romo carried the career pedigree of a top reliever who closed out a World Series and, just as importantly, seemed open-minded about the idea.

On May 19, 2018, Romo struck out Zack Cozart, Mike Trout and Justin Upton of the Los Angeles Angels in a perfect first inning. The Rays won the game 5-3. Romo started again the next day, throwing a scoreless 1⅓ innings, though Tampa Bay lost 5-2.

Some saw the opener as the latest savvy experiment by the analytical Rays. Other more traditionalist baseball fans criticized the team’s lack of closer and set rotation. Among the most pointed criticism came from an elite big league starter: Astros righty Zack Greinke.

“It’s really smart, but it’s also really bad for baseball,” Greinke, then with the Arizona Diamondbacks, told Bleacher Report’s Scott Miller. “There’s always ways to get a little advantage, but the main problem I have with it is you do it that way, then you’ll end up never paying any player what he’s worth because you’re not going to have guys starting, you’re not going to have guys throwing innings. You just keep shuffling guys in and out, so nobody will ever get paid.”

It worked well enough that Tampa Bay kept the practice up for the rest of the season. That year, Tampa Bay was the only team to use an opener in the double digits, employing the strategy in 41 games. In 2019, six teams used openers in double-digit games, led by the Rays at 57 times. What started as a fringe strategy had become mainstream, particularly in the playoffs. This October, the Yankees attempted to use an opener to trick Tampa Bay in the ALDS, starting rookie righty Deivi Garcia before bringing in J.A. Happ in the second inning of Game 2 — a move that ultimately backfired.

With a rotation topped by the talents of 2018 Cy Young winner Blake Snell, Glasnow and Charlie Morton, the rest of the Rays’ Swiss Army knife pitching staff has been tasked with simply getting outs, regardless of situation or inning.

That philosophy has shaped the rest of the Rays’ roster.

“Try to appreciate the strengths a player possesses at any given moment,” Neander said. “Try to keep the focus there. Try to think about the paths to further development. You don’t necessarily know what they’re going to take, but the more options, the more possibilities, the more you have a chance for them to take that step. It’s easy on any given player to focus on what they can’t do, especially prospects.”

The Mariners saw Ryan Yarbrough as a soft-tossing lefty minor leaguer with little upside. The Rays saw a pitcher who, with his plus control, could be an up-and-down guy at the minimum. The Rays got Yarbrough and Mallex Smith for Drew Smyly (who promptly got injured). Meanwhile, Yarbrough added a cutter to help against righties, and that has become his best pitch as he has gone 28-16 with a 3.94 ERA over three seasons.

“The fact is that when everyone gets traded, the first thing they say is they do extremely well at developing pitchers, and the fact that I come over and we were able to hone some things and figure out some ways to get better, it was the truth,” Yarbrough said. “It was a great job, and you can see all of the guys who have come up through the years and had a lot of pitching success.”

“We’re good because we have good players and we really work hard to get them in the right positions to be successful and win you games. But the bottom line is that you don’t get to this point and you don’t have a record that we have without having good players.”

Rays manager Kevin Cash

The Rays acquired Nick Anderson last season from the Marlins with Trevor Richards for outfield prospect Jesus Sanchez and reliever Ryne Stanek. The Marlins figured they would cash in on a 28-year-old rookie reliever they had acquired for next to nothing from the Twins. The Rays saw a pitcher, who no matter his circuitous route to the majors (including time in independent ball) had great stuff and the potential to be one of the best relievers in baseball. Anderson has a 1.43 ERA in the regular season since that trade, with 67 strikeouts and just five walks in 37 2/3 innings.

The Pirates had grown frustrated with Meadows and Glasnow, even though both were once regarded as top-20 overall prospects. Meadows had been injury-prone in the minors, and the Pirates had given up on Glasnow as a starter due to control problems. The Rays saw two talented — and still young — players who perhaps just needed a change of scenery. They got the pair for Archer in 2018, in what looks like one of the best trades of the past few years.

Yandy Diaz had just one home run in 265 at-bats with Cleveland in 2017-18, plus he was blocked at third base by Jose Ramirez. The Rays saw a player who had big exit velocity, plate discipline, could play third or first and just needed to add some loft to his swing. They got Diaz in a three-way deal, giving up Jake Bauers. Diaz has hit .278/.365/.451 with a 121 OPS+ with the Rays — the perfect complementary player.

When asked about his relationship with the team’s front office, manager Kevin Cash — a former journeyman catcher for teams including the Rays, Red Sox and Yankees, and who later served as a Toronto Blue Jays scout and then Cleveland’s bullpen coach — described the dynamic as “a collaboration,” noting a running conversation between the player development, scouting, front office and coaching groups, with ideas pitched — and heard — from all sides.

“That’s where Erik Neander and his staff do such a good job of bringing that all together,” Cash said. “You watch Erik and how he goes about his day, and we’re around each other a lot right now in this bubble, but for every single conversation he has with a scout, he has with an R&D guy. He’s trying to pull as many thoughts together as possible so we can make really good decisions on the baseball field.”

The results of this year’s playoffs bear the fruit of this work, with outfielder Randy Arozarena tearing up fastballs left and right and part-time players like Mike Brosseau coming through with a series-defining home run against the Yankees in the ALDS. The Rays have long needed to find value between the cracks, spending significant time scouting a player’s personality and character to supplement any interest sparked by the analytics.

Cash said that the approach to roster building shaped an underdog mentality within the clubhouse, with many players overlooked by other teams finally getting an opportunity with the Rays. He typically finds that when a player joins Tampa Bay, it doesn’t take very long for him to buy into the team’s culture. And while Cash understands how analytics shaped the reputation of his team, that doesn’t define the players in his clubhouse.

“I don’t think we outsmart clubs,” Cash said. “We’re good because we have good players and we really work hard to get them in the right positions to be successful and win you games. But the bottom line is that you don’t get to this point and you don’t have a record that we have without having good players.”

Maddon’s Rays wrote the first chapters of the franchise, but Cash’s team is now trying to start a legacy by winning a World Series.

En route to the franchise’s second Fall Classic appearance, Cash removed an All-Star starter with a big-game pedigree — Morton — in Game 7 after 5 2/3 innings and 66 pitches, and runners on the corners with two outs, eliciting immediate criticism of the move on social media.

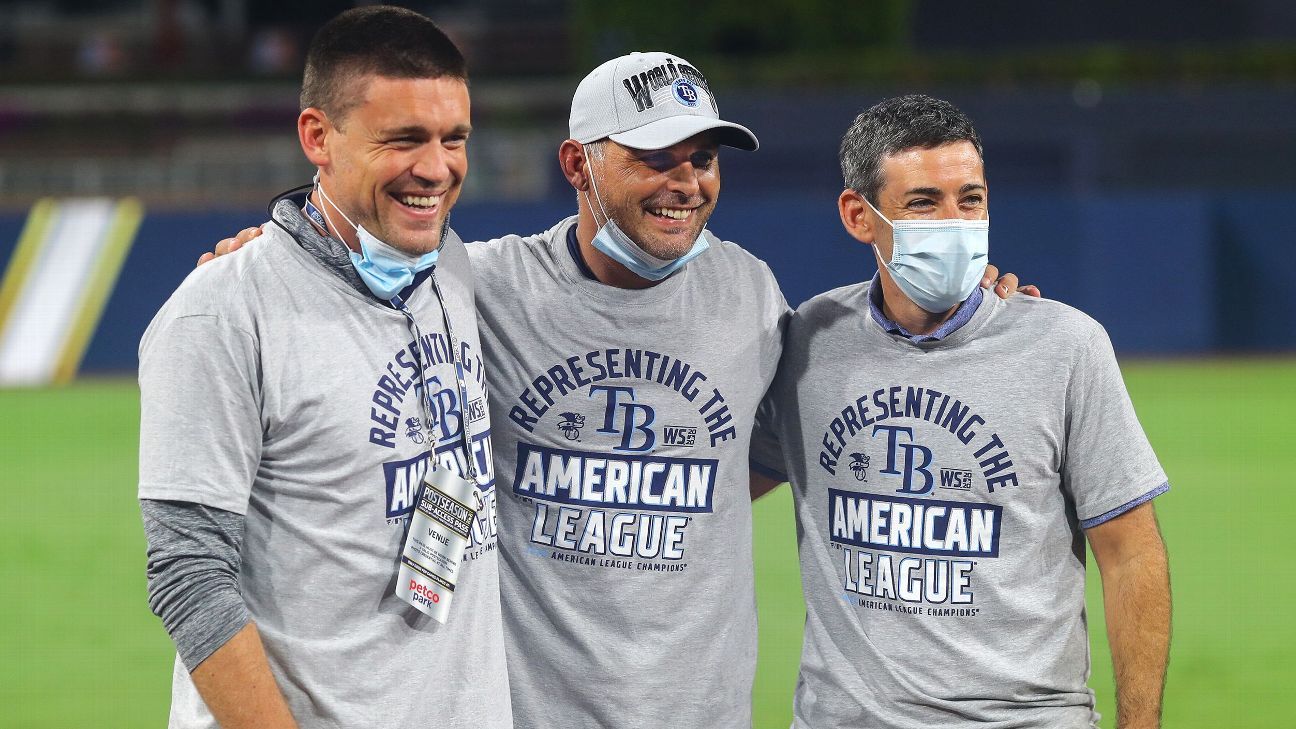

Cash brought in Anderson, trusting that Tampa Bay’s process would bring another victory after a season in which the Rays posted the AL’s best record (40-20), trusting that his best reliever would get him out of the game’s most important situation instead of allowing Morton to face Astros hitters a third time around. Anderson got the out, and three innings later, the Rays celebrated on the field at San Diego’s Petco Park, with a ticket to Arlington, Texas.

When asked after the game why he removed Morton, Cash got right to the point.

“It was pretty simple. Third time through [the order], we value that. We value our process,” he said. “We believe in our process, and we’re going to stick to that.”