THE CENTERPIECE OF the Las Vegas Raiders‘ Allegiant Stadium is the 95-foot Al Davis Memorial Torch. Built out of carbon fiber and aluminum and billed as the largest 3D-printed object in the world, the urinal-shaped cauldron doesn’t feature an actual flame. Encircled by a bar, like all serious monuments, it instead blows a mixture of hot air and lasers to simulate flames in front of the $1.9 billion stadium’s lanai-style peep show doors that open to expose the Strip. The rest of the building is adorned with a similar kind of classic Vegas casino-style art meant to assimilate the Raiders into the culture of their new hometown. The works include an Area 51 alien sporting Raiders merch and one particularly riveting piece featuring Baby Carlos of “The Hangover” sporting a Raiders beanie. There’s a mural of Raiders greats and a series of ayahuasca-fever-dream-inspired murals by local artist Michael Godard that reimagine Marilyn Monroe as a Raiderette, Wayne Newton as a Silver and Black quarterback and Elvis Presley as a Raiders running back.

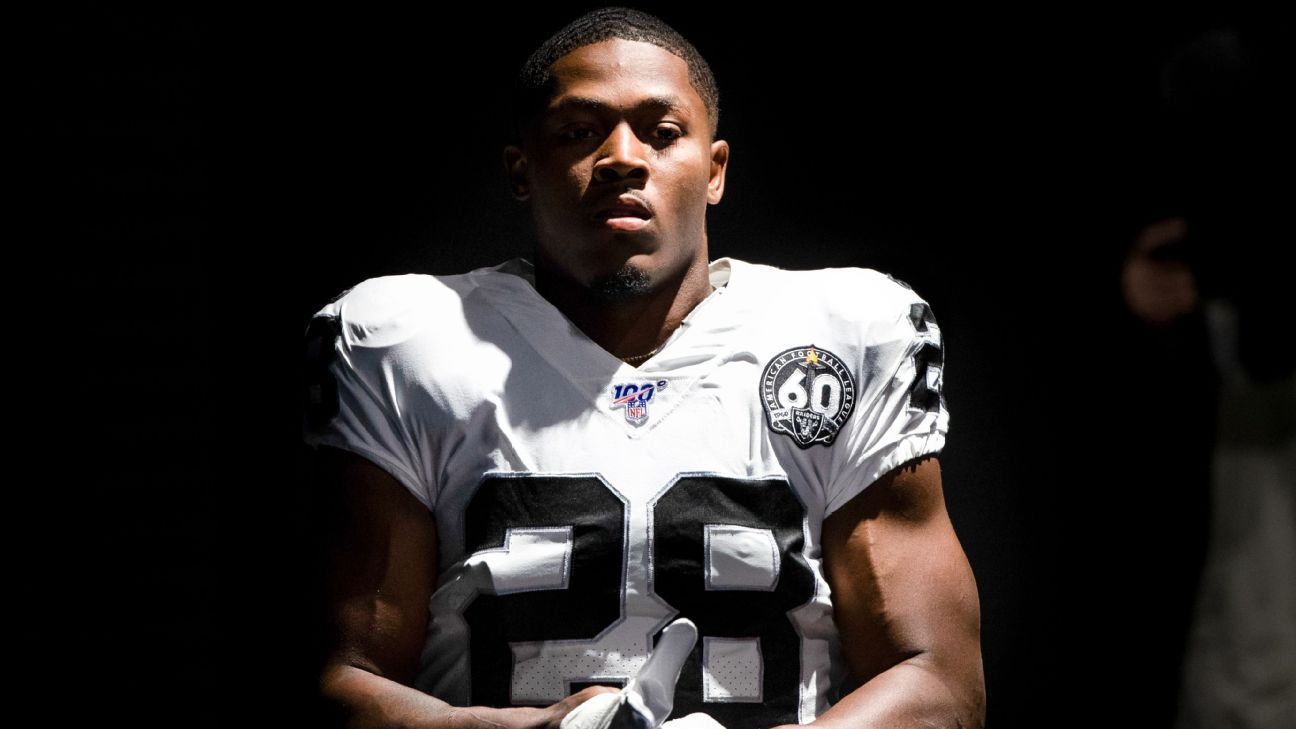

And just in case there’s any question as to just how impossibly high the expectations are for the Raiders’ inaugural season in Vegas, one of the few other locals deemed worthy of a King-sized portrait inside Allegiant is Raiders running back Josh Jacobs, whose picture towers above what seems like a mile of white marble near the corner suites on the 200 level of the stadium. “Very surreal and humbling,” Jacobs says about his portrait. Taken 24th overall out of Alabama in last year’s draft, Jacobs set the franchise record for rookie rushing yards (1,150) and led the NFL in missed tackles (70), all while playing most of the season with a broken shoulder. Now the writing is quite literally on the wall for him and the 2020 Raiders.

In a Week 1 win against Carolina, Jacobs responded to the expectations by scoring three touchdowns and breaking 10 more tackles on his way to 139 all-purpose yards. It was a performance so explosive and dominant, yet somehow so effortless and smooth, that it drew comparisons to yet another GOAT. “That was a little bit like Walter Payton used to play,” says coach Jon Gruden. “Josh is special. He deserves some national attention, and I hope you give it to him.”

Jacobs is one of the most compelling success stories in the NFL and, pound for pound, one of the game’s most physical young runners, and Gruden and the Raiders are now counting on him to develop into the kind of dynamic all-around talent worthy of becoming the national face of the franchise, or, in Vegas vernacular, the town’s first Chairman of the Scoreboard. “Josh is going to be a superstar,” says Raiders fullback Alec Ingold. “There’s a really, really unique opportunity that none of us will probably ever get in our lifetimes again of setting the foundation and the identity for what the first Las Vegas Raiders teams will be. And in a lot of ways, that’s the responsibility Josh has taken on. He really makes this offense run, and he sets the tone for what this franchise is going to be in our new home.”

Even with the questionable decor choices, the Raiders’ new home base, which makes its debut on Monday Night Football against the New Orleans Saints (8:15 p.m. ET on ESPN), is nothing short of spectacular. The expansive locker room, featuring long club-style ceiling lights crisscrossing above the center of the room, feels like something befitting of Marshmello, not Maxx Crosby — although there are already nine other clubs inside the stadium, including one so close to the north end zone that Gruden could easily signal its bouncers to break up any potential Hail Marys. “This is our field of dreams,” says owner Mark Davis. “This is our house.”

For Jacobs, though, it was only the second-best dream house reveal of the offseason. In January, he bought his father, Marty, a house in Oklahoma, creating a fairy-tale ending to a well-documented journey that began 10 years ago on the streets of north Tulsa inside the family’s red Chevy Suburban. When Josh was in middle school, he and his four siblings and Marty were homeless for several weeks. After their parents’ divorce, Josh and his siblings initially stayed with their mother, Lachelle. Josh says they argued frequently, however, especially over what he says was Lachelle’s misuse of child support money. Eventually Marty was granted custody of his kids, just as he found himself between apartments and jobs. It’s an all-too-common scenario experienced by many of the nearly 60,000 families in the U.S. that are homeless on any given night, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Jacobses crashed with friends and in motels as long as they could until they were forced to sleep in the Suburban in a section of town where Josh had been shot at as a teenager. “I wouldn’t change how I grew up for nothing because it made me who I am today,” Jacobs says. “Nobody can tell me that something isn’t possible, and I’ve got so many other dreams I want to achieve, starting with a championship, so I’m still grinding in every aspect of life.”‘

To this day, Jacobs vividly recalls — in a way that suggests the experience is never far from his thoughts — that his father would often go without food, waving it away and pretending not to be hungry, so his children would have fuller bellies. Marty would often go without sleep as well, standing guard in the front seat with a gun resting in his lap, his eyes bloodshot from exhaustion and stress. Ten years later, after the surprise gift from Josh, when Marty’s eyes were watering again, this time he was leaning against the black-and-gray granite countertops inside his immaculate new kitchen as giggles from grandchildren echoed throughout his spacious new home.

Standing next to him, and close to tears as well, was a former homeless teenager turned NFL running back who has now christened new homes for both his father and his franchise. “The kids that warm your heart as a coach are the ones who were not given anything and had to earn everything,” says former Alabama offensive coordinator Mike Locksley, now the head coach at Maryland. “I saw Josh, going from homeless to buying his dad a house, and it’s especially heartwarming when the reason you got into this business is to change people’s lives with this brown football.”

To help his kids process their emotions throughout their childhood, Marty encouraged them to express their feelings through poetry and art. Josh responded by drawing a picture of his dad valiantly fighting off a series of monsters. To this day, Josh attacks most carries on the football field in the same fashion: as an opportunity to slay some monsters, or at least run them over. Throughout his career, despite his relatively small stature (5-foot-10, 212 pounds), Jacobs has left in his wake a breathtakingly violent, “Jackass”-esque compilation of cartoonishly destroyed would-be tacklers. Just ask the Panthers. Against Carolina, an astonishing 87% of Jacobs’ 93 yards rushing came after contact. “There’s no doubt he is an angry runner,” says Locksley, who now coaches Josh’s younger brother, Isaiah. “It’s a chip on his shoulder, angry at the world, here I am a kid that spent time being homeless, not heavily recruited out of high school, then, at Bama, not being the focal point of the offense. Every time he touches the ball, he runs as if he may not get the ball again.”

In 2015, as an unknown Wildcat quarterback at McLain High School in Tulsa, Jacobs was putting up truly unbelievable numbers. His stats were so off-the-charts ridiculous, in fact, that a skeptical reporter called McLain’s athletic director and accused football coach Jarvis Payne of padding Jacobs’ stats. It’s a frequently recurring accusation in Jacobs’ life. “The more you get to know him,” Ingold says, “the more he does seem too good to be true almost.” Jacobs’ high school stats had to be doctored. How could a no-star, injury-prone kid suddenly average 300 rushing yards a game?

“Well, come to our next game and see for yourself,” Payne growled into the phone. Just before kickoff against Cascia Hall Prep, Payne went to Jacobs’ locker and dropped the details of the phone call. “After that I felt kind of sorry for that team,” Payne says. “Josh took everything out on them.”

The stats in question were, in fact, way off. Instead of a measly 300 yards, Jacobs ended up with 455 on 22 carries. And it would have been north of 600 if several big runs hadn’t been called back. After a breathtaking display of speed, power, elusiveness and, well, controlled rage, on Jacobs’ sixth and final TD, a clear path to the end zone emerged. Instead, and in what would become his signature move as a running back, Jacobs lowered his shoulder and bulldozed a defensive back who was left straddling the goal line like a Dali timepiece. “Poor kid,” Payne says. “Josh could have easily sidestepped him and walked into the end zone, but he chose to run him directly over. I’ve seen a lot of talented kids, but that level of anger and tenacity? Very few are built like that. Josh needed to prove a point to the world. And that kid was in his way.”

Several weeks later, when former Alabama and current New York Giants assistant coach Burton Burns sat down to watch McLain’s highly ranked basketball team’s practice, Jacobs took the ball end to end, effortlessly gliding around defenders before finishing with so much power to the basket that his forearm ended up above the rim. Burns got up and sprinted to his car like he was about to get towed, and after a frantic call to Nick Saban, Jacobs was bound for Tuscaloosa. “I see it in him, that extra hunger, that inner spark and inner sense of drive that is not typical unless you’ve been in those shoes,” says Arash Ghafoori, the executive director at the Nevada Partnership for Homeless Youth, which runs a drop-in center just a few miles from Allegiant Stadium. “I see it over and over: The experience of being homeless doesn’t beat these kids; they beat the experience, and then that resiliency becomes part of their DNA.”

After splitting time in Saban’s talent-rich backfield, Jacobs burst onto the scene during Bama’s 2018 run to the title game. When an Auburn cornerback attempted to tackle Jacobs in the open field, the defender eventually came to rest on his head, with the rest of his body facing the wrong way, a full 7 yards downfield. A few weeks later in the national semifinal, Jacobs road-graded an Oklahoma safety on his way to pay dirt. Jacobs’ personal favorite came next, in the title game, when he pancaked a 280-pound Clemson defensive end, then flexed over his massive, prostrate body. “He was a lot bigger than me, so I was supposed to lose that battle,” Jacobs says. “So I put him in the ground and then, yeah, I flexed on him. Honestly, yeah, it feels good.”

0:58

Before Raiders running back Josh Jacobs starred at Alabama and in the NFL, he was torching high school defenses.

Jacobs’ signature as a runner (and blocker) is the way he is somehow able to crystallize his physical gifts and the residual anger, fear and intense drive (along with even the tiniest perceived slight from an opponent, à la Michael Jordan) into a force that, when transferred into the body of would-be tacklers, often leaves them several yards downfield looking as if they’ve just been ejected from a mechanical bull.

Last season, in a Week 7 matchup at Lambeau Field, Packers safety Adrian Amos stepped in front of Jacobs at the 22. Amos, who made the unforgivable mistake of getting too much attention for being one of the highest-paid safeties in the game, returned to earth somewhere around the 26. For starters, Jacobs believes in the age-old runner’s argument that operating at anything less than full speed is far more dangerous. “That’s when injuries happen,” he says, “when you’re going through the motions.” And he insists he could have easily made Amos miss — if he’d wanted to. But Jacobs’ uber-violence is more about inspiring his teammates and dictating the chess game in the trenches. After he runs over a tackler or two, the entire Raiders offense operates on a different plane, while the defenders, obsessed with delivering a huge payback blow, are overextended and off balance. “Then I’m gonna juke ’em and make them look stupid,” Jacobs says. “So it’s all a mind game.”

Two plays later, in fact, Jacobs reeled off a 42-yard run to set up the Raiders’ first score. But the damage had been done. This wasn’t Cascia Hall Prep. The showdown with Amos had left Jacobs with a fractured right shoulder. “It hurt,” Jacobs confesses. “But that’s football.” In a feat that seems nearly superhuman given the pain involved and the relentless pounding delivered to a running back’s shoulder, Jacobs valiantly continued to play — and play well — for the next five weeks. Although pain-killing injections deserve some of the credit, playing through the injury earned Jacobs the kind of universal locker room respect and stature that usually takes younger players years to acquire. “That’s another weight that Josh has to carry is that he’s the focal point of this offense and also this team’s identity,” Ingold says. “So when you say he runs with all that anger and he runs people over even when he doesn’t have to, it’s not just Josh, it’s the Raiders. He has to set the standard for the rest of us.”

Over time, though, Jacobs’ shoulder deteriorated to the point that he missed three of Oakland’s final four games, and the Raiders faded from playoff contention, finishing 7-9. It was the franchise’s 15th non-winning season in the past 16 years. When the doctors finally forced him to sit out, Jacobs was sobbing so hard his entire body was shaking inside his locker. He felt lost again, unmoored. His calling card as a runner had become his kryptonite. And with his life off the field near perfect, moving forward he would have to learn to run with purpose instead of anger. As crazy as it sounds for someone who dealt with homelessness as a child, the toughest challenge of Jacobs’ life was still ahead of him: adapting and surviving in a league in which most running backs are battered and broken and discarded before they hit 30. (Case in point: Leonard Fournette, the No. 4 pick in the 2017 draft, was cut in camp by the hapless Jaguars before signing with Tampa Bay.)

Sometimes, Jacobs learned, the actual work begins after all your dreams come true. “I’m gonna be one of those guys who walks away with my body intact,” Jacobs insists. “I’m not gonna be one of those guys who plays until he’s 35 and all of that. I plan on leaving on my terms. And my running style? Not only does that come from my life, it comes from people trying to confine me and put me in some kind of box, like ‘You’re this kind of runner, you’re that type of runner.'”

Jacobs’ shoulder injury opened the door for Cardinals quarterback Kyler Murray to win 2019 Rookie of the Year honors. Jacobs, who finished third in the NFL with 88.5 yards per game, would award himself only a B for his rookie season. Rather than bask in his success and the realization of a lifelong dream of buying his dad a house, after the season Jacobs went to Gruden and, instead of a pat on the back, asked for a shove.

Chucky was, of course, more than happy to oblige.

“He’s got to stay healthy,” Gruden says. “We need our feature back down the stretch. We were in a playoff stretch last year and didn’t have him. He’s got to stay wire-to-wire healthy, and we have to get more out of him in the passing game, more on the field on third downs. He had a great year last year, and we expect more from him this year.”

Gruden’s message seems to have gotten through — a little. On the fourth day of camp, Jacobs caught a pass in the flat and began to lower his shoulder preparing to steamroll then-teammate Damarious Randall, only to pull up at the last second to smartly avoid a collision. It was a sign, however small, that Jacobs has begun to manage those cravings for contact and run with focus instead of fury. Of course, after the play, Jacobs barked, “Boom! I just retired you” just to remind everyone that the détente was a temporary courtesy, and only for teammates.

To further reduce Jacobs’ wear and tear and increase his production — as well as his Q-rating — Gruden plans to get him much more involved in the passing game. The goal is to increase his 20 catches in 2019 to 60 this season. His four catches in the opener put him on pace for 64. If he stays on that pace and gains another 1,000 yards on the ground, that combo would put Jacobs in rare company, alongside versatile All-Pro-level backs such as Christian McCaffrey and Ezekiel Elliott.

It’s a skill set Jacobs has been developing for years. Back in Tulsa, before his senior season at McLain, when Payne realized Jacobs had a better arm than any of his quarterbacks, the coach (and robotics teacher) recircuited his entire offense and moved Jacobs to Wildcat quarterback. The improvement was instant. “And ridiculous,” Payne says. “Like watching a human highlight film.” For good measure, Jacobs also started at safety and even found time to contribute on special teams and pitch in with some game strategy consulting.

In 2015, in a late-season game with playoff implications, McLain had the ball at the 30 with the score tied and time about to run out. McLain hadn’t kicked a field goal all season, so Payne had already begun making plans for overtime when, instead of taking a knee, his quarterback called timeout and trotted to the sideline. “Hey, Coach, let’s kick it,” Jacobs said. “I’ve been watching our kicker and working with him — he can make it.” Payne huddled the team together and drew up a makeshift field goal formation using Jacobs as a decoy. Thinking it had to be a trick play, the defense didn’t bother to rush the kicker. “He lines up, takes his time and kicks the most perfect 30-yard field goal you will ever see in your life,” Payne says. “Josh brings out the best in everyone, even the kickers, even the coaches.”

At Bama, to get Jacobs more opportunities while sharing time on a roster loaded with future NFL playmakers, Locksley used him as a back, as a slot receiver, on pass protection, on special teams and even at quarterback. “And he was good at everything,” the coach says. “As an offensive coordinator, he’s just one of those rare chess pieces. I call him Swiss Army Knife because he’s just so multifaceted.”

More from David Fleming:

The untold stories of Jock Jams, 25 years later

The promise of family for Marquise and Morgan Goodwin

The six words of trash talk that made ‘The Last Dance’ possible

It’s a trait that applies to Jacobs’ entire life. Wanting to expand his interests off the field, this summer Jacobs met with several businessmen and entrepreneurs who, he says, always had the same response: “Are you sure you’re only 22?” Teammates swear he can hit 15 3-pointers in a row on a basketball court. On his first carry in camp, after nearly falling on his face, Jacobs put one hand on the ground, caught his balance and blew through the Raiders’ defense. “We all just looked at each other like, ‘Oh my god,'” Ingold says. “The first time you see his kind of power and acceleration, it’s like watching a new Ferrari leave the shop.” A few days later, when Raiders back Jalen Richard visited Jacobs’ home outside of Vegas, Jacobs was playing piano and preparing chicken and shrimp fried rice from scratch. “So what can’t you do?” Richard said with a laugh.

Before the Raiders had even completed their move to Vegas, Jacobs had already worked with the Nevada governor and attorney general to produce child ID kits to prevent human trafficking in a region with the country’s highest rates of youth homelessness. Just before the 2019 draft, when it looked as if Jacobs was headed to Las Vegas, a die-hard Raiders fan and volunteer at the Nevada Partnership for Homeless Youth emailed Ghafoori, the NPHY director. The Raiders are going to have someone on their team who could have literally been one of your kids at NPHY, the email said. “I looked Josh up and read his story and I got goose bumps,” Ghafoori says. “The Raiders have their own unique history in terms of having multiple homes. … The Raiders could make a huge impact in Nevada, and Josh could be our biggest game-changer.”

Ultimately it will be up to Gruden whether Jacobs has a similar impact on the Raiders franchise. When it comes to incorporating running backs into the passing game, many NFL schemes still operate like nickel slots at the Flamingo: low risk, low reward. Even in today’s pass-happy NFL, contributing in the passing game for running backs mostly means serving as a safety valve checkdown for quarterbacks. (The Giants are constantly neutralizing Saquon Barkley this way.) Dumping the ball off on simple flare-outs, rub routes and shallow crosses to a dynamic talent like Jacobs is essentially a gift to defenses, reducing his power and impact by forcing him to move horizontally and allowing the sideline to become a 12th defender instead of attacking defenses vertically and capitalizing on the constant mismatches Jacobs’ skill set creates.

Instead, the model for the Raiders should be McCaffery, who, like Jacobs, played multiple positions in high school and lined up 100 times as a slot receiver during his rookie season. That dual threat, in turn, prevents defenses from loading up the box to stop the run. In the opener, Jacobs and McCaffery led their teams with 139 and 135 yards from scrimmage, respectively. (Don’t be surprised, by the way, if Gruden also uses Jacobs under center. “I’m not gonna sit here and tell you he’s Jim Plunkett,” Locksley says, “but Josh is definitely skilled enough to throw the ball.”)

So it’s a hopeful sign that when asked about his offseason training focus, Jacobs sounds more like a receiver geek than a running back. Former NFL running back and current Raiders wide receivers coach Edgar Bennett constantly fed Jacobs film cut-ups on the art of receiving. One day Jacobs would watch film on disciplined route stems to prevent telegraphing his routes, the next he’d study release techniques for press coverage or how to read body language and create leverage to attack defensive backs downfield. Jacobs even dove into “stacking” — an advanced technique to manipulate defensive backs in the deep passing game.

If there was any doubt Jacobs had truly upgraded his route-running and receiving game, it ended in Carolina when he vaporized linebacker Shaq Thompson with a surgical cut up the seam for a 29-yard catch. It was one of a dozen highlights in an all-around performance that Jacobs says is just a glimpse of what he plans to unveil in 2020. “In college and high school, I played everything, so it’s just about getting back to that,” Jacobs says. “I don’t want to be known as just a good runner. I’m more than that. I didn’t do enough last year, and I left a lot of yards on the table. This year is going to be different for me. I’m going to become a complete player and take my game to the next level.”

Tonight, with the national spotlight focused on Allegiant Stadium, the 2020 Raiders and their franchise back, as the previous King of Vegas once said: It’s now or never.