TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — The text messages on Greg Byrne’s cellphone were pouring in, more than 1,000 and counting.

Like most around the college football world, Alabama’s athletic director was still processing what had transpired about 2½ hours earlier that afternoon.

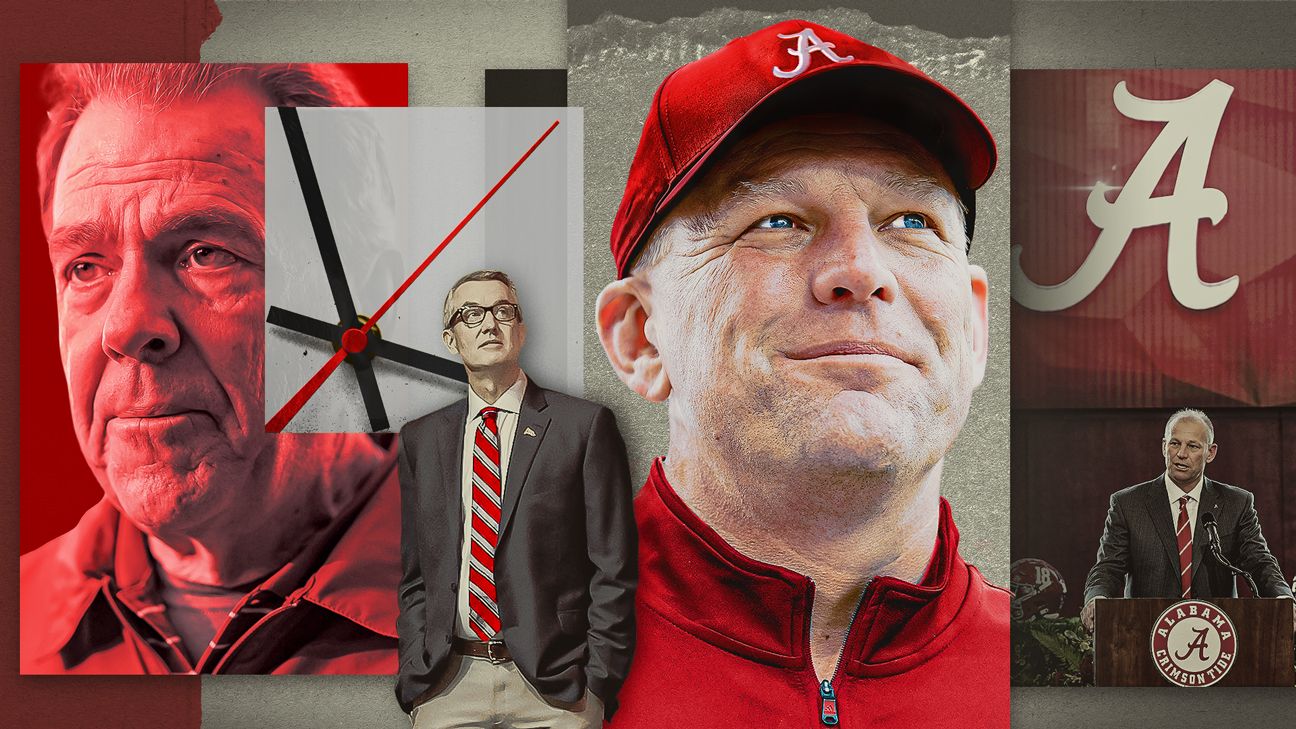

Nick Saban had walked into the team meeting room at the Mal M. Moore Athletic Facility and told his players he was retiring. After 17 seasons, 206 wins, nine SEC championships and six national titles at Alabama, one of the greatest coaching runs in American sports history was over.

And Byrne was on the clock.

He understood the enormity of what he was tasked with, the momentous challenge of hiring the replacement for a legend.

“When you’re approaching a historic transition like that, you think about when Coach [Bear] Bryant retired, when John Wooden retired, but it’s also different now because of the transfer portal and NIL,” Byrne said. “But from an impact on a university and the sport itself, it’s as big a change as there has been in a long time.”

Saban spoke with his players for six minutes before leaving the room. Byrne then told the team he would have a new coach in place within 72 hours.

“It ended up being 49. I thought I would beat the 72-hour window but wanted to give myself some padding,” Byrne said.

Saban’s meeting with his players ended at 5:06 p.m. ET on Jan. 10. At 6:06 p.m. ET on Jan. 12, Byrne posted a photo on social media with smoke rising from a chimney — like the Vatican does when there’s a new pope, except this time it was the chimney of a Tuscaloosa barbecue joint — confirming that Washington’s Kalen DeBoer was Saban’s replacement.

Through conversations with the principals involved and other industry sources, ESPN retraced that head-spinning week, which ushered in a new era of Alabama football and, in some ways, reshaped the landscape of the entire sport.

BYRNE’S TWO-DAY WHIRLWIND was actually a year in the making. After the 2022 season, Saban informed Byrne he was nearing the end of his Hall of Fame coaching career.

“Greg, this is getting more and more difficult on me,” Saban told Byrne. “I’m not ready to do it now, but we’re going to have to start evaluating this more on a year-to-year basis.”

While hopeful Saban would keep coaching, Byrne knew deep down that the 72-year-old legend was giving him notice, so he quickly went to work. Byrne had his staff research the college head-coaching hires over the past 25 years from the winningest 25 programs during that span.

“Part of what I was trying to understand is what were the analytics, and our studies showed that 75% of the time you’re basically hiring a Group of 5 head coach, Power 5 coordinator or NFL coordinator,” Byrne said. “That’s not necessarily a negative, but when it comes to the theory that you’re going to hire just whoever you want, the percentages don’t support that.”

Then again, this was Alabama, so the Tide could set their sights higher than most any other school.

By Bama’s standards, the start of last season was a struggle, but Saban was exceedingly proud of how much the team improved. The Tide reeled off 11 straight wins, culminating with a 27-24 victory over Georgia in the SEC title game, snapping the two-time defending national champion Bulldogs’ 29-game winning streak.

“We weren’t a very good team those first few weeks of the season, but it’s a credit to those kids how far they came,” Saban said. “I’m not sure I’ve had a team that improved more over the course of the season.”

But the 27-20 overtime loss to Michigan in the CFP semifinal at the Rose Bowl on Jan. 1 was a hard one for Saban to digest. Not only was Saban upset about the way his team played, he was especially disheartened about some of the things that happened afterward — in the Rose Bowl locker room and back on campus when he met with some of the players.

“I want to be clear that wasn’t the reason, but some of those events certainly contributed,” Saban said of his decision to retire. “I was really disappointed in the way that the players acted after the game. You gotta win with class. You gotta lose with class. We had our opportunities to win the game and we didn’t do it, and then showing your ass and being frustrated and throwing helmets and doing that stuff … that’s not who we are and what we’ve promoted in our program.”

Once back in Tuscaloosa, as Saban began meeting with players, it became even more apparent to him that his message wasn’t resonating like it once did.

“I thought we could have a hell of a team next year, and then maybe 70 or 80 percent of the players you talk to, all they want to know is two things: What assurances do I have that I’m going to play because they’re thinking about transferring, and how much are you going to pay me?” Saban recounted. “Our program here was always built on how much value can we create for your future and your personal development, academic success in graduating and developing an NFL career on the field.

“So I’m saying to myself, ‘Maybe this doesn’t work anymore, that the goals and aspirations are just different and that it’s all about how much money can I make as a college player?’ I’m not saying that’s bad. I’m not saying it’s wrong, I’m just saying that’s never been what we were all about, and it’s not why we had success through the years.”

Saban had also grown weary of churning through assistant coaches every year. For example, Tommy Rees, who was hired during the 2023 offseason, was Saban’s seventh offensive coordinator in the past 11 years, and on occasion, there were nearly entire overhauls. After the 2018 season, seven assistants left for other jobs. Saban could tell that his age was becoming a factor in hiring coaches.

“People wanted assurances that I was going to be here for three or four years, and it became harder to make those assurances,” Saban said. “But the thing I loved about coaching the most was the relationships that you had with players, and those things didn’t seem to have the same meaning as they once did.”

Saban and his wife, Terry, left for their home in Jupiter Island, Florida, on Thursday, Jan. 4, two days after flying back from Los Angeles. They always get away for several days right after the season, but this trip was different.

“That’s one of the reasons we went, to discuss whether I would keep coaching,” Saban said. “But she didn’t know. I didn’t really know. It’s just not something I think about during the season, but that was the time to think about it and talk about it, for both of us.”

They returned to Tuscaloosa the next Monday night, Jan. 8. During their time in Florida, there were some deep conversations but no final decision.

“I don’t know if there’s ever a good time to do it,” Saban said. “I felt like my age was starting to impact a lot of things. The older you get, the harder it is to sustain it at the level you want to and feel like you’re doing a great job.”

While in Florida, Saban said he talked to Hall of Fame coach Bill Parcells, who has a home in that area. Saban said he also talked with former Alabama coach Gene Stallings about his decision.

“Both of them said you never know quite when it’s the right time, but you kind of also know in the back of your mind when it’s the right time,” Saban said. “And that’s sort of the way I was feeling.”

Still wrestling with his decision, Saban called Byrne while he was in Florida and asked whether he would be in Tuscaloosa on Tuesday. Typically when they met, Byrne would drop by Saban’s office because Saban was always so tied up with football-related duties. But this time, Saban went to see Byrne in his office. They talked for nearly an hour.

“I wasn’t going to believe it until I heard it from him for sure, and he still didn’t say it was for sure,” Byrne said.

But Byrne knew where things seemed to be heading.

On Wednesday, Jan. 10, Saban was in his office at his regular time, around 7 a.m. Even staff members who had been with him the longest said it was business as usual.

“But that’s just him. He was going to work right up until the very end, and that’s what he did,” said head athletic trainer Jeff Allen, who came to Alabama with Saban in 2007. “It’s a big part of why he’s the best to ever do it, that singular focus.”

Saban met with people on his staff that Wednesday and conducted Zoom interviews with prospective assistant coaches. The gravity of what he was planning to do was surreal even for him.

“I’m sitting there looking at the clock, talking to Ms. Terry, and you know you’ve got a team meeting coming up. I guess I still wasn’t 100 percent sure,” Saban said. “I thought it was the right time for us. I didn’t like how it would impact the program, the players, the coaches, the people in the organization, the university. That part of it was really hard. But it was inevitable that it was going to happen at some point in time, and I didn’t want to ride the program down.

“It was just the right time.”

SABAN WAS ADAMANT that his players hear the news from him first, and he addressed them in the team meeting room. Byrne and members of the Alabama football staff also were present. There was an eerie hush as Saban exited the room, and Byrne then stepped to the podium and spoke to the players. He later met with the team’s leadership group, then conducted an internal meeting with administrative staff members in his conference room.

As Byrne left campus Wednesday evening, he began reaching out to former players from different eras. He talked to Joe Namath, Mark Ingram, Jalen Hurts and DeVonta Smith.

“Not to discuss candidates, but it was more, ‘What do you think if you were in my shoes?'” Byrne said. “Because they may have had a piece of information I hadn’t thought about, which is good.”

Equally important, Byrne said, was the alignment at the university with president Stuart Bell and the board of trustees.

“We were all ready and all on the same page,” Byrne said.

From the outset, Washington’s DeBoer and Florida State’s Mike Norvell were at the top of Byrne’s list. Both had what Byrne was looking for: a proven head coach who had won on a big stage and shown the propensity to develop players. Byrne declined to go into detail about whom he talked to first or his pecking order. But he had serious conversations with both coaches the day after Saban retired.

Throughout the interview process, Byrne was in contact with Bell as well as with Saban and Mike Brock, the athletics committee chair of the board of trustees. Byrne had to deal with only one agent as Jimmy Sexton represents both DeBoer and Norvell.

Immediately, there was speculation that Clemson’s Dabo Swinney and Ole Miss’ Lane Kiffin were possible candidates. Swinney played and coached at Alabama, and Kiffin worked at Alabama under Saban. Both were part of national championship teams at Alabama.

Byrne said there were conversations in his circle about a handful of candidates, but sources told ESPN that neither Swinney nor Kiffin was seriously in the mix. Texas’ Steve Sarkisian, who, like Kiffin, is also represented by Sexton, was another prominent name mentioned in media reports, but Alabama’s leadership knew Sarkisian wasn’t going to leave Texas, especially with the Longhorns moving to the SEC next season, sources said.

As expected, Sarkisian sent out a social media post at 11:50 p.m. ET that Thursday saying it was a great day to be a Longhorn with a “Horns up” image. A day later, ESPN reported that Sarkisian was nearing a deal for a contract extension with Texas.

Oregon’s Dan Lanning, who worked as a graduate assistant under Saban at Alabama, made it clear earlier Thursday that he wasn’t a candidate despite erroneous reports that he had been spotted in Tuscaloosa. Lanning, also represented by Sexton, released a video at noon Thursday confirming that he was staying put after two seasons in Eugene.

It didn’t really matter, though, because by that time Byrne was bearing down on his top two targets. He and his wife, Regina, met with DeBoer and his wife, Nicole, on Thursday in downtown Seattle. There were also serious discussions with Norvell that day.

In fact, in the wee hours of that Friday morning, the fear among Florida State officials was that Norvell was close to trading his FSU garnet for Alabama crimson. Sources told ESPN that Florida State was poised to move quickly if that happened and that Kiffin would be a prime candidate.

Norvell, who in his fourth season at FSU led the Seminoles to a 13-1 record and ACC championship, declined to say whether he was offered the Alabama job, but he acknowledged to ESPN later Friday afternoon that the past 24 hours had been chaotic as he considered his options.

“You respect the place. You respect the position,” Norvell said of Alabama. “At the end of the day, it still comes down to the right fit. It still comes down to the place you want to be.”

There were sighs of relief around FSU’s campus when athletic director Michael Alford posted a tweet at 11:51 a.m. Friday that indicated a deal with Norvell was in place. Then at 12:07 p.m., Norvell took to social media to confirm he was staying put.

Shortly thereafter, news broke that Norvell had agreed to an extension on his contract that would pay him more than $10 million annually over the next eight years. Part of the agreement was a reassurance to Norvell that more money would be committed for his football administrative staff and a larger recruiting budget. A new stand-alone football complex was already under construction, along with upgrades to the stadium.

DeBOER’S EMOTIONS HAD run the gamut since the final seconds ticked off the clock at the national championship game in Houston. His Washington team fell one win short of a title, losing 34-13 to Michigan.

As the Huskies returned to Seattle the next morning, DeBoer said the last thing on his mind was that he might be on the verge of changing jobs. After all, it felt as if he was just starting his climb at Washington. The year before he arrived, the Huskies were 4-8.

“I mean, that Tuesday was hard,” DeBoer said. “We’re flying back from the game, and you’re just trying to get yourself back. I was texting kids on the plane just about how I felt about ’em, how strong I felt, especially the guys that were done with their careers. You’re working through all of that.”

On Wednesday morning, DeBoer woke up in the Pacific Northwest refreshed and ready to go.

“I was like, ‘OK, quit feeling sorry for yourself and let’s get up and let’s go. We’ve got to go win this thing. There’s another step here at Washington,'” DeBoer told himself.

Little did he know that his world was about to change over the next 48 hours. Early that afternoon (West Coast time), DeBoer heard the news that Saban was retiring.

“It wasn’t even on my radar, not sure it was on anybody’s radar,” DeBoer said. “And then immediately when it happened, people from all over start calling and you’re getting all these questions. I guess I knew with everything we’d accomplished that you might have some inquiries about jobs — but not that one.”

Later Wednesday evening, DeBoer got the initial call that Alabama was interested in talking. He had never met Byrne, but Byrne had long been a fan of DeBoer’s and the way he had won everywhere he’d been, including grinding his way through the NAIA ranks.

“It just happened so fast, all of it,” DeBoer said. “I get the call Wednesday night they want to talk. We’re meeting on Thursday morning, and I was offered the job on Friday morning. I didn’t have time to talk to a lot of people. I just knew I wanted the job.”

One of the first questions Byrne asked DeBoer during their Thursday meeting was the inevitable: “How do you respond to the narrative that you never want to be the one who follows a legend but rather the one that follows the one who follows the legend?”

DeBoer’s response was exactly what Byrne wanted to hear.

“I’m going to embrace it,” DeBoer said. “There’s only one person that’s ever going to get to do that.”

Washington did its best to keep DeBoer, who rejected two contract offers from the Huskies. The first one came during the season, when DeBoer passed on an extension that would have taken him to a maximum of $9 million annually. The final rejection came that Thursday during Alabama’s talks with DeBoer, when Washington offered a base salary of $9 million that would have maxed out at $9.6 million. DeBoer earned $4.2 million last fall. His buyout was $12 million.

When DeBoer was offered the job Friday morning, one of the first calls he made was to Saban.

“I picked up the phone and reached out,” DeBoer said. “It was great, just, out of respect. I hope he knows how much it means to me to be coming in behind him.”

By 2 p.m. ET Friday, Alabama was finalizing a deal with DeBoer. He told his players later that afternoon that he was taking the Alabama job before boarding a private jet bound for Tuscaloosa that evening.

“The hardest part is when you get put in that spot where the call does come, especially this one just because now you’re a head coach,” DeBoer said. “You’re not a coordinator going to a head-coaching job. You’re not at a Group of 5 school where you’re going from Fresno State to Washington. This was the toughest one of them all.

“We loved Washington, the people there, our players, everything we’d accomplished in two years. But I also just loved everything about Greg Byrne and our conversation together and everything that Alabama football stands for, the proud tradition of this program and how deep it runs.”

When DeBoer climbed off the jet in Tuscaloosa, fans were lining the fences at the airport to congratulate him. Later that evening, he met with the Alabama team for the first time.

“I hope you appreciate what you’re a part of,” DeBoer told the players. “That’s why I wanted to be here. This place is not normal. It’s special.”

Even before his first day on campus was over, he knew the short-term challenges ahead were already piling up.

Key players were entering the transfer portal or talking about it, and coaches were leaving. Two of the Tide’s most promising young players left within a week of DeBoer’s hiring, safety Caleb Downs to Ohio State and offensive tackle Kadyn Proctor to Iowa. There were also coaches coming and going, as DeBoer worked to assemble his staff and had to go through two waves of hiring assistants.

One of the things that was so heartening to DeBoer during that time was the way some of the pillars on Alabama’s team — Tyler Booker, Deontae Lawson, Malachi Moore and Jalen Milroe — remained committed during all the changes.

“We’ve embraced the change and, as a group, want to finish what we started,” Lawson told ESPN. “We’re not running from change. We’re buying in and know we’re in good hands. We have full trust in Coach DeBoer and the coaches he’s bringing in.”

DeBoer understands how some would look at the sheer number of players leaving during that time — 10 players entered the portal in the nine days after Saban’s announcement, and more than 25 did over the course of the offseason — and think Alabama’s ship was taking on water. But he never viewed it that way.

“We had about 30 guys, and those are rough numbers, that have come into the program, and actually more than that when you count the guys coming in this summer,” said DeBoer, adding that Alabama might add some players during the spring portal. “There was some attrition that needed to happen, and some of it was happening before I even got this job.”

With his first spring practice at Alabama opening earlier this week, DeBoer said he hasn’t spent any time thinking about everything that led him to the Tide. He just knows he’s here and ready to take on perhaps the biggest challenge any coach has ever faced in college football.

“I couldn’t say no to that challenge,” DeBoer said.