FORT MYERS, Fla. — Carlos Correa had been feeling great — really, he felt spectacular. At the end of a long season, he had been working out without issues, even playing tennis with his sister, as he waited to see how his free agency played out. And so he is the first to acknowledge: The collapse of the record-setting $350 million deal with the San Francisco Giants was a stunner. Correa had assumed that passing the Giants’ physical examination was a fait accompli. “I’m like, ‘Easy money,'” Correa recalled.

Then, after the Giants’ retreat, New York Mets owner Steve Cohen swooped in with a $315 million offer — but that, too, disintegrated, over doctors’ doubts about the leg injury nearly a decade old. “The second one was more shocking,” Correa said. To his understanding, the Mets had made the agreement knowing about the leg concern.

“When it fell through, it was like, ‘Oh, s—.'”

The series of events was unprecedented, a superstar and his value tumbling into negotiation vertigo, and Correa needed certainty. He told his agent, “Hey, take me where I’m wanted.”

And so it came to pass that Correa ambled back into the Minnesota Twins‘ camp earlier this spring, a place few thought he’d have ever entered in the first place. From the early days of Correa’s career, the industry assumption was the former No. 1 overall pick — an ambitious prodigy who asked his parents at age 8 for English lessons so that he’d be equipped to conduct second-language interviews as an adult — would find his way onto the biggest and brightest stage possible, almost certainly in New York or L.A. or Wrigley Field.

But now he is likely to spend the rest of his career in Minneapolis, and the Twins’ staffers, who had gotten to know Correa in what they assumed would be a one-and-done season of 2022, felt the depth of his commitment immediately. Correa’s present and future are settled and he’s all-in, intent on winning as much as possible — and on playing as much as possible, now that he’s absorbed the feedback from doctors about his leg. Correa has shaped his career with analytics — he loves, uses and relies on numbers — and understands risk management. So based on what he’s heard from those doctors and his own, he’s already started to adapt.

“We are not going to play tennis anymore,” he said of those offseason sessions with his sister. “I am not going to play basketball anymore. We aren’t going to do these things that are outside the box of my profession. It’s about being smarter than that.”

Correa is a giant among shortstops, 6-foot-4 and 220 pounds, and he readily acknowledges that he’ll eventually move to third base (a switch he would’ve made if he had signed with the Mets). If he could benefit from less time on his feet, a reduction in his workout regimen — the sort of mid-career career change that has helped Aaron Judge, among others — then he’s intent on figuring it out. He’ll learn how to do more with less. The failed physicals are part of his history now, but any anger, any frustration over the way his winter played out have been effectively compartmentalized. He is moving on.

“You know, there’s not many things that will bring me down,” Correa said, sitting at a picnic table next to a half-field at the Twins’ complex. “I don’t focus on what’s outside. I focus on what’s inside. By saying inside, I mean my family members, my friends, my teammates and the people that truly are in my safe place.

“I always say that the boat will never sink into the water that surrounds it. The water you let get into your life, that’s what’s going to sink your boat. All that outside noise and all the outside stuff that I cannot control, it’s never affected me. I just keep going on with life, and I keep trying to make a positive impact with the people around me.”

THE DAY BEFORE Correa had arrived in the Twins’ camp, he had been alerted by the team that some media members would be there to document the return of a player now anointed — through the sheer magnitude of his contract — as an heir to Kirby Puckett and Joe Mauer and Justin Morneau.

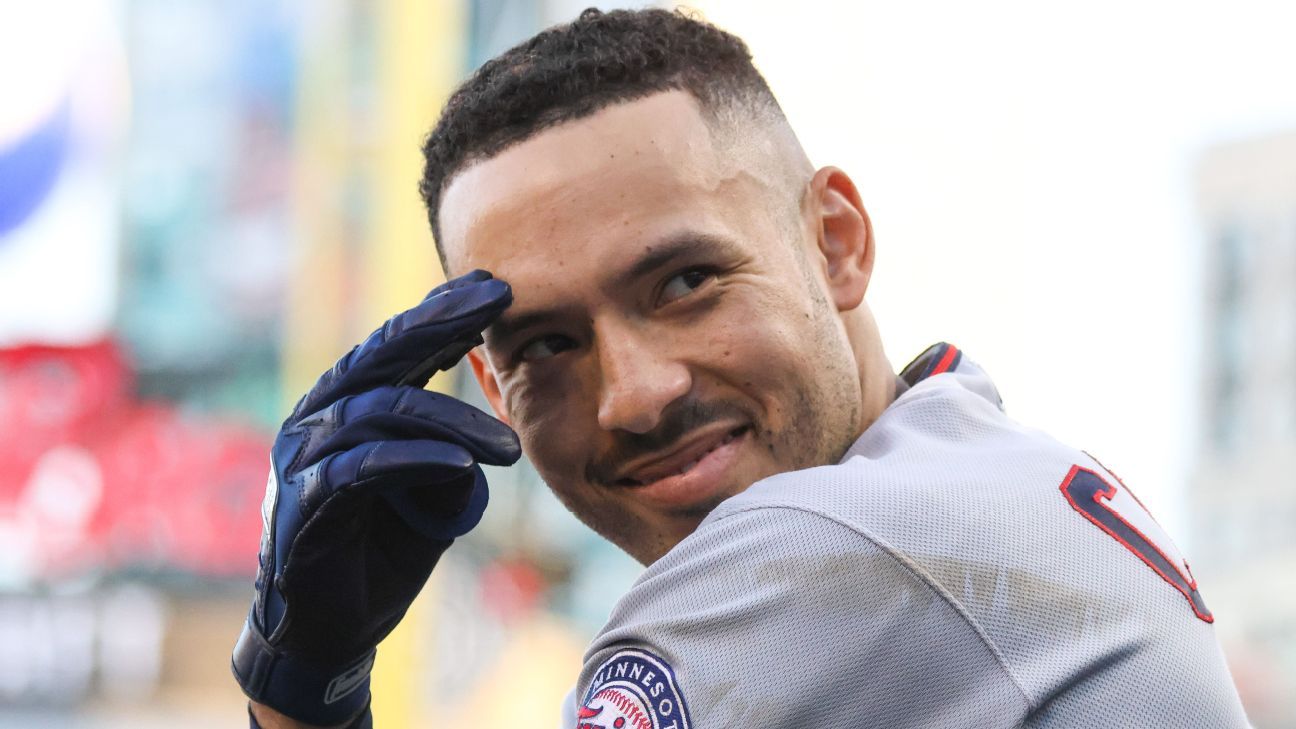

He told them he would come through the clubhouse doors at 8:45 a.m., and as it turned out, his ETA was off. At 8:44, Correa stepped into the room. His personality filled the room as he greeted old and new teammates with handshakes and hugs. Twins pitcher Sonny Gray had texted during the chaos of Correa’s winter, asking Correa how he was doing, and at that time, Gray said, the idea that Correa might return to Minnesota was never raised. It wasn’t a thought. “But he’s here now,” Gray said, smiling, talking about how Correa, center fielder Byron Buxton and new catcher Christian Vazquez will anchor a strong defense. Not long after Correa had set down his bag in the corner locker of the Twins’ clubhouse, he went out to the cages for swings, his voice resonating about the echoes of bat cracks. Then Correa jogged out to the half-field where three coaches waited for him, and he shouted happily and cajoled as he gloved and whipped baseballs through a series of drills. Then he stopped by a small group of fans to sign autographs.

“I’m glad you’re back, Carlos,” one of them said.

“Me, too,” he replied.

He worked his way from one end of the pack to the other, inking baseballs and cards. He passed over a card type he recognized and said evenly to its owner, “I already signed one for you, sir.”

Minnesota nice.

After the owners’ lockout ended last spring, the Twins signed Correa to a three-year deal. But the contract contained an opt-out clause and the assumption within the organization was that there was a high probability he would leave after the 2022 season. The Twins offered $285 million early in the offseason, but the industry expectation was that Correa might get an offer that would set a record for shortstops — likely beyond the Twins’ comfort level. Which is what occurred.

Just before the news broke that Correa had agreed to terms on a 13-year, $350 million deal with the Giants in mid-December, Correa’s agent, Scott Boras, reached out to Derek Falvey, the head of baseball operations for the Twins, and gave him a heads-up. Falvey texted Correa with congratulations, and this: “If you have a few minutes, I’d love to catch up.”

Right away, Correa phoned Falvey, and over the next few minutes, Falvey conveyed how happy he was for the player, for his family, and he thanked Correa for his time in Minnesota. Falvey heard emotion in Correa’s response. “There was a little bit of him that was still connected to the Twins,” Falvey recalled.

Little more than a week later, Falvey was preparing to introduce free agent signing Joey Gallo to the Twins when he got a text from a reporter asking if he had heard anything about Correa’s press conference in San Francisco being interrupted. Falvey, unsure of what the reporter was talking about, checked his news feed and saw a reference to a California earthquake. Maybe the seismic event had been the holdup, Falvey wondered.

But later, as more specific information emerged about how the Giants had canceled the scheduled press conference, Falvey reached out to Boras. The agent asked Falvey if the Twins’ last offer — the $285 million deal — remained on the table. Falvey, unsure about what had blown up the Giants’ deal, was non-committal, particularly without having a conversation with his bosses. The next morning, Falvey turned on his phone to get another message from Boras. Overnight, the agent had quickly arranged the 12-year deal with the Mets. But as that deal stalled too, Falvey kept in touch with Boras. Doctors consulted by the Giants and Mets had raised red flags about the long-term impact of a broken right fibula that Correa suffered in 2014, and whether his movement on the field will be significantly diminished as the 28-year-old moves beyond his early 30s. One rival team official with knowledge of Correa’s exams said, “Years 1 through 3 look fine. The short-term looks fine. It’s the middle part and back end of his [long-term] deal that is the concern.”

Minnesota by then was alert to the same medical information that had scared the Giants and Mets, but Falvey and his front office also knew this about Correa after having him in their clubhouse on a daily basis: He would change his physical regimen as needed. Correa had reached out to Dr. Robert Watkins, a spine surgeon who has worked with several MLB players, while having debilitating back trouble in his time with the Astros. After that consultation, Correa developed a strength-and-stretching program that he adheres to religiously — as good of a regimen, Falvey felt, as he had ever seen.

In the end, the Twins cut their offer in guaranteed dollars to Correa by about 30%, though their amended proposal was much higher than that of New York.

Correa agreed to a six-year, $200 million deal, with a series of four options that can vest based on whether he reached plate appearance benchmarks from year to year. Correa can trigger a $25 million vesting option for 2029 by accumulating 575 plate appearances in 2028. For an additional $20 million in 2030, he needs 550 plate appearances in 2029. He could get $15 million in 2031 if he has 525 plate appearances in 2030. And if he has 502 plate appearances in 2031, he’ll make $10 million in 2032, the year he turns 38.

FOR FALVEY, RETAINING Correa was about more than the value he’d bring on the field. He had also seen firsthand the effect he could have on young minor leaguers. When Falvey had met with Correa early in the offseason, near the outset of his free agency, Correa had asked about the Minnesota’s minor leaguers, about the next-level metrics in their production. Falvey knew the implication of the request — if Correa returned to the Twins, he would want to help educate players on what mattered most in performance.

The locker next to Correa’s in the Twins’ camp is inhabited by first baseman Jose Miranda, who, like Correa, was born and raised in Puerto Rico.

When Miranda was promoted to the big leagues last year, Correa noted one of his statistics from the minor leagues — Miranda’s on-base percentage — and asked the slugger if he could identify the most important numbers generated by his performance. What followed was a Correa primer on modern analytics, which he takes very seriously.

“From that moment I met him during the season when [Miranda] was called up, he was exactly like me,” Correa said, explaining his morning Internet searches. A visit to baseballreference.com, Correa said. Then Fangraphs. Then Baseball Savant. “You check all of your stats every single day,” Correa counseled Miranda. “That’s how you understand it, right? … You start understanding the game, and you start playing for these metrics that we are getting judged on. At the end of the day, it’s going to determine how much money you make.”

During his time with the Astros, Correa had asked to meet with some of the team’s analysts, quizzing them about the statistics most germane to his performance. Correa — who had thrived as a student, scoring a 1560 on his SATs — was immediately drawn to the numbers. One Astros staffer from Correa’s time with Houston said that the player’s knowledge was so acute that he could immediately calculate within a game how a particular play could impact his overall WAR. Correa confirmed this in a conversation this spring and recalled how he explained this to Miranda, how the statistics ultimately shaped the numbers on his paycheck — something that Correa believes all players should understand.

“In order for me to get players to buy into the analytics, I got to talk to money,” he said. “I’ve got to talk WAR, because that’s how we get valued in this game, right?”

To understand the depth of Correa’s fluency in statistics, you should know it’s part of at least one rival’s scouting report on the All-Star shortstop. Correa was on first base in a possible running situation last season, and one of the staffers in the opposing dugout said out loud: “No, he’s not going to run. Because he understands the statistical impact of getting thrown out.” A failed stolen-base attempt hurts the team’s chances of winning, as the analysts explained to Correa; it hurts his own numbers. Correa has attempted one stolen base in the past three years.

“Stealing bases has no value unless you’re going to steal 50 bags and not get caught at all,” Correa said. “That has a lot of value, right? If you steal 10 bags and get caught seven times, it’s going to hurt you big-time on your WAR. It obviously hurts you more getting caught stealing, but what I tell the players is that in today’s game if you want to win, you have to do whatever you need to help your chances for winning.

“You’ve got to walk … When you get to the playoffs, … it’s hard to string three, four, five hits together, right? But you can get a walk here, a walk there, and all of sudden a three-run homer. Then you’re winning that game.”

Correa leaned forward, his elbows on the picnic table. He was on a roll, focused, talking about winning. The Twins haven’t celebrated a World Series title in more than 30 years, but in the earliest days of his return to Ft. Myers there was Correa talking out loud with staffers about winning a championship. Or two. Or more. Pushing, nudging, leading, his halogen personality revealing a path he’s taken before, when he became a champion with the Houston Astros. Now, he’ll do it with more information than ever before on his own future and the obstacles ahead.

“It’s just things you have to do, to do the work you have to do on the field,” Correa continued. “You know — rest, mobility work, strengthening the areas around it, and a healthy diet. That’s the key about success in this game — the players that are willing to do all the hard things to be successful, and not everybody is willing to go to bed early, wake up ready to work, wanting to eat a healthy diet. There’s always something more you can do. When you look at the elite of the elites in the game … that’s really what sets them apart and gives them the advantage.”

For the Twins, having Carlos Correa for the foreseeable future is an advantage they never anticipated. But he is here now, and into a baseball future that he will work to lengthen.