ANTONIO LANGHAM GLANCED across a crowded hotel ballroom in downtown Atlanta and noticed an older, white-haired gentleman slowly walking in his direction. Langham, a household name in Alabama football lore, was being honored that weekend as the Crimson Tide’s “SEC Legend” on the eve of the 2009 SEC championship game. The older gentleman walking toward Langham was Roy Kramer, and Langham sheepishly admits that he didn’t immediately recognize the former SEC commissioner.

But make no mistake: The pair will forever be linked.

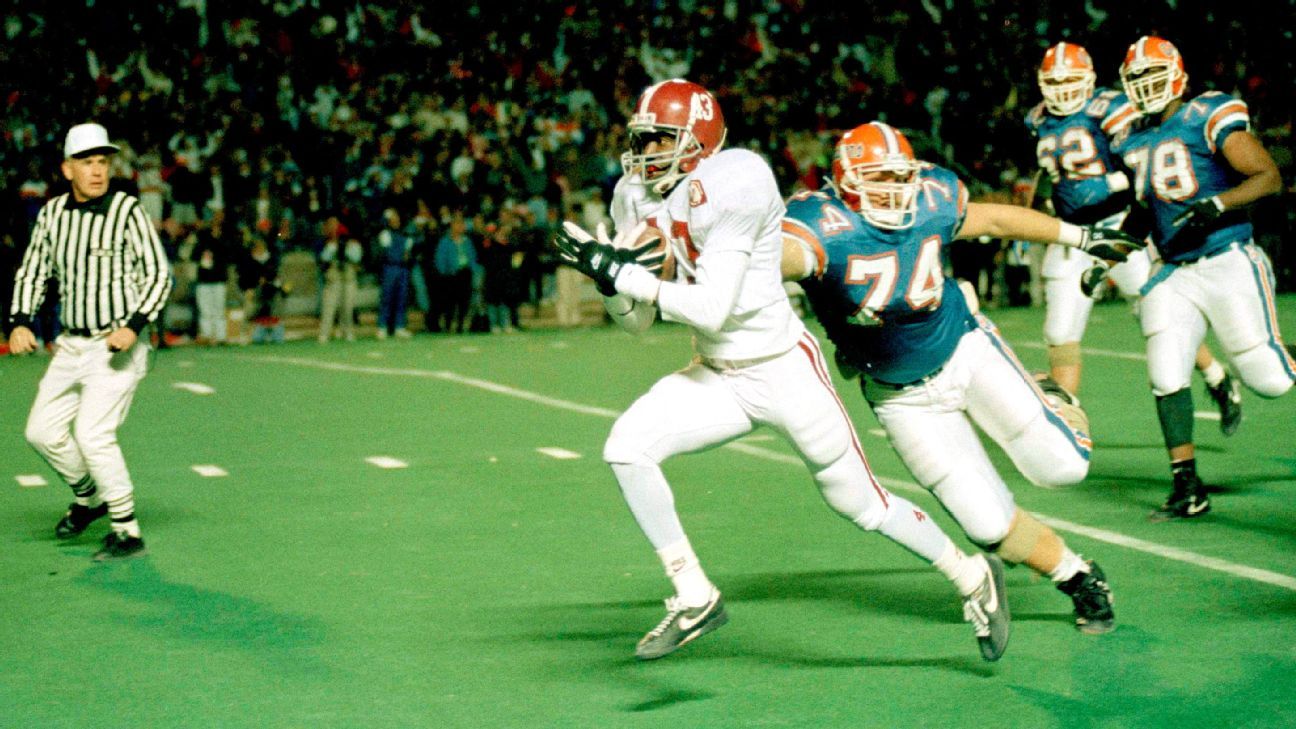

It was 30 years ago that Langham’s 27-yard interception return for a touchdown saved Alabama in the inaugural SEC championship game, a thrilling 28-21 victory over Florida. The unbeaten Crimson Tide went on to win their first national championship in the post-Bear Bryant era when they defeated Miami 34-13 in the Sugar Bowl. Langham’s memorable pick-six may have also saved Kramer, who came up with the creative (and controversial) idea of playing a conference championship game after the SEC expanded to 12 teams in 1992, not to mention setting in motion the model that still is at the center of determining the national champ.

“We were at the banquet the night before the game, and I’m just mingling after we’re all up on the stage and see him coming toward me with his arms out,” Langham said. “I look around and am thinking, ‘Who’s he walking over to hug?’ I know it’s bad to say, but I had no clue who Commissioner Kramer was. I mean, I had met him before, but I sort of stepped out of the way because I thought he was looking for somebody else.”

But Kramer knew exactly who he was looking for, the guy who wore No. 43 for Alabama on that cold, rainy night in Birmingham’s Legion Field in a game that shaped college football more than anybody could have known at the time.

“Antonio, I just want to hug your neck,” Kramer told Langham with a hearty laugh. “You are my favorite athlete of all time.”

IT WAS A HUGE GAMBLE by Kramer and the SEC to add a championship game in 1992. They were the first major conference to do so after finding a little-known NCAA bylaw that stipulated a conference with 12 teams could split into two divisions and play a championship game. The SEC had just added Arkansas and South Carolina as its 11th and 12th members.

“The bylaw was originally put in for Division III conferences, but it applied to everybody,” Kramer said. “Once we hit 12 teams, we knew we could take advantage of it, and I knew it wouldn’t be popular with everyone in the sport, even in our conference. But our teams having a chance to potentially play for two championships at the end of the season, the conference championship and the national championship, was something that gave a flair to our conference that was unique at the time.”

So unique that then-Florida coach Steve Spurrier asked, “Is that even legal? Commissioner Kramer assured me that it was, and I guess a lot of the growth and changes we see today in college football goes back to that game.” Spurrier was one of the few coaches in the SEC at the time who liked the idea.

“Oh, I loved it. There’s nothing like a championship game,” said Spurrier, who revels in telling the story about a charity golf tournament he played in around that time with then-North Carolina basketball coach Dean Smith and then-Kansas basketball coach Roy Williams.

“Coach Smith asked, ‘Are you guys going to get a playoff in football?'” Spurrier said. “I told him I didn’t know, that everybody just sort of plays their season, then the bowls come in and pick the teams they want, and then after they play, they get a bunch of sportswriters together and they vote on who’s national champion.”

The Head Ball Coach then looked at his two Hall of Fame hoops counterparts and asked his own question: “How would you boys in basketball like it if you did it like that?”

Smith looked at Spurrier and quipped, “We wouldn’t, because that’s stupid.”

In retrospect, Spurrier would wholeheartedly agree.

“Maybe that SEC championship game Commissioner Kramer came up with got the ball rolling,” Spurrier said. “At least we’ve got a little bit of a playoff scheme now to determine the champ.”

Most of the coaches in the SEC hated the idea of a conference championship game, and Alabama’s Gene Stallings was especially upset. Their fear was that the SEC was putting itself at a decided disadvantage in the national championship race by playing an extra game.

“We were 11-0 and hadn’t won anything,” recalled Stallings, now 87 and living on his farm in Paris, Texas. “I remember thinking how hard it was going to make it for the SEC to win another national title, but Roy knew what he was doing.

“I’d say it’s worked out just fine because you’re not going to find a better environment or a better showcase for college football than the SEC championship game each year.”

And that 1992 title game paved the way for the SEC to win 16 of the next 30 national championships, with six schools winning titles.

It was such a novel concept at the time, though, that nobody around the sport knew what to make of it.

“I don’t think any of us had really thought about it,” former Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany said. “Give credit to Roy, though. He had a vision, and it’s a game that carries a lot of marketing weight and a lot of financial weight. I think the SEC is very, very proud of their game. They were the first to have one, and it’s part of their culture.

“It’s probably as important to them as the Rose Bowl is to us.”

The Big Ten began expansion conversations with Penn State in 1989, but the Nittany Lions didn’t begin play in the conference until 1993. Delany said there wasn’t a concerted effort to go from 11 to 12 just to add a conference playoff. In fact, the Big Ten didn’t expand again until 2011, when Nebraska came aboard, and it started its conference championship game that season.

In 1996, the Big 12 was the next major conference after the SEC to add a championship game, following the merger of the Big Eight and four teams from the old Southwest Conference. More dominoes fell with the ACC adding Virginia Tech, Miami and Boston College and playing its first conference championship game in 2005. The first Pac-12 conference championship game was played in 2011 after the league grew to 12 teams with the additions of Utah and Colorado.

“It’s interesting that some of the most vocal opponents to some of these moves, even the long resistors, have their own championship game,” said current SEC commissioner Greg Sankey, who helped craft a 12-team College Football Playoff expansion proposal that was voted down in February by the short-lived Alliance (ACC, Big Ten and Pac-12). The CFP will remain at four teams through the end of its current contract, which runs through the 2025 season.

“When we first went down the conference championship game road, we felt our game would be a way for our teams to play their way into the national championship game,” said Mark Womack, Kramer’s right-hand man who remains the SEC’s executive associate commissioner.

“Now, everything else that has happened in our sport, conferences getting bigger and bigger and having their own TV networks, I don’t think we quite foresaw the unprecedented change in what we’re seeing right now in college athletics. We thought our conference championship game might precipitate some change, but nothing like this.”

THE ONLY THING on Kramer’s mind that Dec. 5 night nearly three decades ago was that he might get run out of town if a three-loss Florida team managed to upset Alabama and ruin the Crimson Tide’s national title hopes. The Gators got the ball back in the final minutes of a tie game with a chance to take the lead when Langham stepped in front of a pass by Florida’s Shane Matthews and took it to the house.

“There was a lot of angst even before the game, a lot of angst, and I’m not sure what the future of the conference championship game would have been had Alabama lost that first one and been knocked out of the national championship,” Kramer said. “Our goal was for that game to serve as a showcase for the SEC, and I think we accomplished that.”

The inaugural SEC championship game was televised nationally by ABC with the legendary Keith Jackson on the call and earned a 9.8 rating, not to mention 83,091 fans packing Legion Field. The game moved to Atlanta in 1994 and has been one of college football’s crown jewels ever since.

A year ago, the SEC championship game between Georgia and Alabama led all conference title games in viewers (15.3 million) and attendance (78,030). The 1992 game generated $6.1 million in total revenue, including TV money, while the 2021 game generated $26.6 million.

“It’s been a great way to celebrate SEC football, fans from all over the conference there and the stadium sold out [for 26 consecutive years],” Womack said. “I would argue that it rivals the national championship game as the best game in college football.”

And, yes, Kramer admits establishing the game was a bit of a gamble, but not the only gamble that night. Langham said he rolled the dice on Matthews’ short pass route, and instead of giving ground and forcing the underneath throw like Alabama’s coverage dictated on the play, he hid behind the Florida receiver and came from the outside to intercept the pass.

“I was gambling, too, because Shane Matthews was a great quarterback and didn’t make mistakes,” said Langham, who is on the 2023 College Football Hall of Fame ballot. “Something just told me to sit on the route. I just wanted to make a play because the last thing you want is Steve Spurrier and those guys driving down the field at the end of the game.”

Langham guesses he’s been to about 90% of the SEC championship games since that first one. He’s always amazed at the way it has grown and takes pride in the fact that the SEC was out front in helping the sport evolve and grow.

As Kramer surveys the current college football landscape, he’s not sure how much credit or blame he deserves from what some labeled a “gimmick” 30 years ago.

Keep in mind that Kramer was also the chief architect of the BCS system, which was launched in 1998 and determined college football’s national champion until the CFP took its place in 2014.

Mike Aresco, the American Athletic Conference commissioner, once described Kramer as “a guy who could always see the future.”

That future continues to change, as conferences are now going away from divisions. The NCAA Division I council announced in May that it would relax its restrictions on conference championship games, paving the way for leagues to avoid title-game matchups determined by division winners and eliminating divisions altogether. The Pac-12 immediately announced its title game this season would pit the two teams with the highest winning percentages.

Even the SEC is focusing on a single-division model with either eight or nine conference games once Oklahoma and Texas join the league.

No matter what that scheduling format looks like or even how CFP expansion turns out, good luck in ever getting the SEC to give up its conference championship game.

“I don’t even want to think about that, because it’s a cultural event for our region, and based on viewership, I’d say for the country,” said Sankey, noting that the SEC title game a year ago was the highest-rated college football game of the season.

“You think about our student-athletes, and they point to this game now. So we have to be careful as we think about change, and I tried to be with the last discussion on playoff expansion, to understand where there are real points of meaning — and not just value that seems transactional — but real meaning. And to me, the SEC championship game has great meaning, and we shouldn’t forget that.”

Kramer is not a big fan of a 12-team playoff because he thinks it would devalue the regular season, and he also said that 16 teams (which is where the SEC and Big Ten will be with this latest round of expansion) is about as big as a conference needs to be.

Delany, who retired as Big Ten commissioner in 2020, tends to agree.

“What Roy did was break through from 10 to 12 members and redefine what a large conference was,” Delany said. “We all grew from there, from 10 to 12 to 14 and now 16. I hope that’s enough. I think it’s very hard to have a conference that’s much larger than 16 because then it becomes a small association.”

Kramer will leave it to others to navigate the future of college football. He’s now 92 and lives on an East Tennessee golf course overlooking scenic Tellico Lake.

“I guess, to some degree, we started all this,” Kramer said. “Some might think it’s good, some not so good.”